After a race-motivated attack takes the life of Vincent Chin, Helen Zia and Detroit activists spark a pan-Asian American movement to seek justice.

“It was as though he had been killed again,” Lily Chin, the grieving mother of a young Chinese-American man named Vincent Chin, said to a group of soon-to-be activists in 1983 Detroit.

It was March 20, 1983, and a disparate group of Asian American citizens had come together at the Golden Star restaurant to discuss a community response to Vincent’s death. Approximately nine months earlier, two white strangers had brutally bludgeoned Vincent, a 27-year-old local draftsman, while hurling racial slurs at him. The attack, which began at Vincent’s bachelor party at the Fancy Pants Lounge in Highland Park, Michigan, culminated with the brutal beating in a McDonald’s parking lot several blocks away.

Vincent, a naturalized U.S. citizen, had succumbed to his injuries on June 23, 1982. His killers, “who had beaten a man to death with a baseball bat on the main street of Detroit,” received probation, plus $3,780 in fines, after being convicted of manslaughter. The judge had rationalized this sentence by saying, “These aren’t the kind of men you send to jail.”

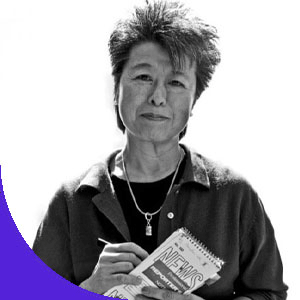

After reading about the myriad injustices surrounding Vincent’s case, Helen Zia—then a Detroit-based Asian American “baby journalist”—wanted to help prevent what had happened to him from befalling other local Asian Americans. She joined Lily and Chinese-American experts, local attorneys, and concerned citizens at the Golden Star to strategize. “We [asked,] ‘how do we get the judge to reconsider his sentence,’ [and] various lawyers said [that almost] never, never, never happens,” Helen says.

That frustrating moment was when Helen—who did not know the Chin family, nor anyone else in the room—felt compelled to speak up.

“When people were all sort of like, ‘No, there’s nothing we can do … to change the sentence,’ I raised my hand. I said, ‘We might not be able to change the sentence, but we have to let people know that the Asian community is not okay with this, that we think this is wrong.’”

Vincent’s mother was “very firm that she wanted to see justice for her son,” Helen recalls. Crying throughout the meeting, Lily Chin also stood up and said, “‘That’s right. We have to let people know.’ That was the beginning,” Helen says today.

**

Days after Vincent’s death, Helen was reading a Detroit newspaper on a typical June morning in 1982. She stopped in her tracks when she first spotted a large, color image of Vincent Chin and his bride-to-be. They’d planned to marry soon, in a large wedding surrounded by hundreds of friends and relatives.

Helen was taken aback to see Vincent’s photo because she recalls, “It was a time when people of Asian descent were completely invisible in America. To see an Asian face in the news was shocking.”

The story didn’t reveal any details behind Vincent’s killing; it just said he’d passed away. She clipped the story out of the newspaper and vowed to follow it closely.

Nine months later, an update about Vincent’s story appeared in the news. When Helen read the truth about Vincent’s death — that it was no accident, and he’d been killed in a race-based attack — she was incensed. Especially when she read the judge’s outrageous comments from the two killers’ sentencing: “These aren’t the kind of men you send to jail. We are talking here about a man who’s held down a responsible job for 17 or 18 years and his son… You don’t make the punishment fit the crime. You make the punishment fit the criminal.”

Helen says, “If these white men are not the kind of men you send to jail for beating somebody to death with a baseball bat and having it witnessed by dozens and dozens of people, then who goes to jail in a city that was 60 to 70% black at the time?”

Another thing that disturbed Helen was that no prosecutor was present at the perpetrators’ sentencing; in fact, the court never notified Vincent’s family that sentencing would occur. Hence, no one was in court to speak on Vincent’s behalf.

This failure of justice sparked outrage among Detroit’s varied Asian-American communities, which were already subjected to torrents of racist hatred. In the early ‘80s, America was still in the throes of a deep recession, as well as an oil crisis. Detroit’s auto industry was previously considered a stable bastion of high-paying jobs with great benefits. But thousands of local auto workers had recently lost their jobs or had their hours cut. Detroit’s unemployment rate hung at 17 percent, and half of the city’s residents were on some type of government assistance. The city’s mayor had even declared a hunger emergency.

Japan, a significant player in the international auto market due to the country’s success in manufacturing fuel-efficient cars, became an easy enemy in many Americans’ eyes. With its successful imports of foreign vehicles, Japan was seen not only as a competitor to Detroit’s “big three” automakers but as a hostile entity threatening the American dream.

Vincent’s murder came in a cultural climate in which “people who looked Japanese all became a moving target in Detroit,” and “people who drove Japanese-made cars, whether they were Asian or not, were shot at on the freeway,” Helen says.

Though they had support from Black civil rights leaders in Detroit, bringing advocates together from local Asian American communities proved challenging because of the heightened threats. The individuals involved had a lot to lose: their jobs, safety, and standing in the community. Helen acknowledges that she was more privileged, with a bigger platform and less at stake than some of her fellow citizens at that first meeting. “The idea that we could be targeted and punished for simply existing was something that was fresh in people’s minds. There was a lot of community dynamic about, ‘Should we speak up about racism in America?’—something that, at that time, was viewed as entirely a dialogue about Black and white.”

With Helen’s help, the momentum sparked by that initial meeting at the Golden Star became a new pan-Asian American civil rights organization: American Citizens for Justice, or ACJ. Until that point, U.S. law failed to recognize the civil rights of Asian Americans. When major organizations like the Michigan chapter of the ACLU told ACJ that Asian Americans were not protected by federal civil rights law, the group began petitioning for the Department of Justice to re-try Vincent’s murder as a civil rights violation.

The AJC organized public rallies to demand justice, attracting press attention. Helen and Lily launched an awareness-raising campaign in the media, which sparked investigative journalists to report on details surrounding Vincent’s murder overlooked by the police and not presented at trial. Then Helen and the activists reached out to Congress. With the support of sympathetic congresspeople and mounting public pressure, the Department of Justice began an investigation into Vincent’s death and the violation of his civil rights.

By November 1983, the Department of Justice indicted Vincent’s attackers on federal civil rights charges. Despite the national movement and push for justice, neither man served jail time for the slaying. However, the civil rights landscape had widened—it now included Asian Americans.

Reflecting on the lasting impact of her—and other activists’—work in Vincent’s case, Helen says, “We had no thought that this might be talked about in the future. … We just knew it was the right thing to do.” Helen’s actions home the idea that, as citizens, it falls on each of us to speak up in the face of hate—even when the legal system doesn’t work in our favor. At times, the simple act of fighting back can set a powerful example for others to do the same.

Though the legal system failed to punish Vincent’s killers effectively, the high-profile case pushed Michigan to change its policy allowing prosecutors to be absent from the courtroom during sentencing. “After the Vincent Chin case, the state of Michigan changed that immediately, [declaring] that a prosecutor had to be present at sentencing,” Helen says. The case also contributed to the widespread use of victim impact statements in court, giving crime victims and their families a chance to share their stories.

Helen, who carried Vincent’s legacy on by entering the speaker circuit and continuing to talk, write, and mobilize about Asian American issues, acknowledges that she and her community were brave to fight the way they did. Her decision to raise her hand at the Golden Star came from a sense of personal responsibility to stand up for what was right. “There’s nothing mysterious about it. [The other activists] were all people just like every one of us. I was a young activist and writer … who raised my hand and said, ‘We might not be able to accomplish everything, but at least we can let people know that this was wrong.’ I think that’s something that any one of us can do.”