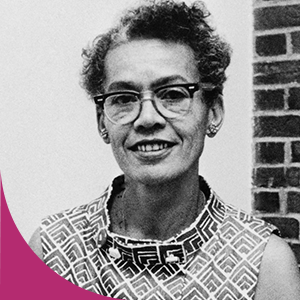

Pauli Murray, repeatedly denied opportunity because of her race and sex, refused to surrender to discrimination. Her vision and dedication helped topple the doctrine of separate but equal, carved a path for women’s rights, and forged a more just America.

“You say I can’t and I’ll show you I can, even if I die trying. This was my attitude toward America.”

Lawyer, activist, poet, and priest Pauli Murray relentlessly did what others told her she could not. Her life was punctuated with firsts that laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights movement. Pauli’s legal analysis and activism set the stage for women to gain equal protection under the law. But her most enduring impact, which would ultimately change the course of U.S. history, may be her steadfast conviction that segregation could be overturned by the Supreme Court using a legal argument rooted in the Fourteenth Amendment.

Growing up as a Black girl in Durham, North Carolina, in the 1910s and 1920s, Pauli experienced racism everywhere, from her grandparents’ stories of the Ku Klux Klan to the “colored” signs over water fountains and bathrooms. Most tragically, Pauli’s father was murdered at the hands of a racist white guard at a grim state-run psychiatric institution. This racially motivated killing stuck with Pauli throughout her life and shaped her lifelong activism against injustice.

By the time she graduated from high school at the top of her class, Pauli was determined to go to college far from the segregated South. “No more segregation for me,” she said later. “I was fifteen, but that I knew.” She graduated from New York’s Hunter College in 1933, one of four Black students in a class of more than two hundred.

Continuing her education became a point of passion for Pauli, but at each brush with academia, she was launched further into activism. In 1938, her application to the graduate school at the University of North Carolina was rejected: “members of your race are not admitted to the University,” the dean’s letter read.

Pauli knew UNC would likely deny her an opportunity to advance her education, but seeing the rejection in print infuriated her. She wrote to the University president and the NAACP, and the story was leaked to the press. UNC’s student newspaper, the Daily Tar Heel, detailed the campus reactions. “I’ve never committed a murder yet,” one student told the paper, “but if a black boy tried to come into my home saying he was a ‘University student…’” Others “vowed that they would tar and feather any ‘n—er’ that tried to come into class” with them.

Pauli penned a scathing response to one of the Daily Tar Heel’s editorials, but her pursuit of justice was cut short when she met with NAACP lawyer (and future Supreme Court Justice) Thurgood Marshall. He explained that Pauli’s case just wasn’t strong enough to mount a legal battle. She was crushed—but she also felt a burden lift.

“Much of my life in the South had been overshadowed by a lurking fear,” she wrote later. “Terrified of the consequences of overt protest against racial segregation,” she had endured its indignities, each one “accompanied by a nagging shame which no amount of personal achievement in other areas could overcome. For me, the real victory of that encounter with the Jim Crow system of the South was the liberation of my mind from years of enslavement.”

Galvanized by UNC’s rejection, Pauli protested segregation on a Virginia bus, campaigned for workers’ rights, and decried the evils of racism in a series of letters to the press and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, with whom Pauli struck up a long friendship and political dialogue.

Though her activist aims drove her, Pauli aspired to be a poet and writer. When she was recruited for law school, Pauli questioned which path to take. Her direction became clear in the summer of 1941 when she stepped into a New York apartment building on her way to a colleague’s funeral, and a doorman insisted she use the service entrance. Racism would follow Black people everywhere, Pauli realized, even to New York City.

Her calling became clear: the only way to escape segregation was to end it. Pauli “went on to Washington to enter law school, with the single-minded intention of destroying Jim Crow.”

Pauli arrived at Howard Law School in 1941 to find that sexism—what she later termed “Jane Crow”—was as persistent an obstacle as racism. Pauli was often mocked, discounted, and excluded by all-male professors and students. But their ridicule only propelled Pauli as she made her way to the top of her class.

In one civil rights seminar, Pauli and her classmates sparred with experienced lawyers on civil rights cases. The class workshopped arguments against Plessy v. Ferguson, the landmark 1896 Supreme Court decision that paved the way for racial segregation. It was during this workshop that Pauli began building the argument that would change the course of U.S. history.

Activists and legal scholars had tried for years to overturn the 1896 Plessy decision, which provided the legal basis for segregation ordinances and unequal access to public facilities, stores, restaurants, transportation, and schools all across the South. When Pauli was in law school, the going theory was that Plessy could only be defeated using case-by-case proofs that “separate” Black facilities were in no way “equal” to their white counterparts.

Pauli proposed a different idea: Plessy should be overturned outright for violating the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. She wrote a legal analysis that was “a frontal attack” on Plessy, arguing that segregation violated “the right not to be set aside or marked with a badge of inferiority.” Segregated facilities relegated Black Americans to a lesser legal and social position. “Having no legal precedents to rely on, I cited references to psychological and sociological data supporting my assertion.”

Her classmates were shocked. It just couldn’t be done, they scoffed. But their derision only impassioned Pauli: “Opposition to an idea I care deeply about always aroused my latent mule-headedness,” Pauli wrote later. Her classmates laughed as she made a ten-dollar wager with her professor. Within twenty-five years, Pauli bet, Plessy would be overturned.

After graduating from law school, Pauli was hired by the Methodist Church to create a pamphlet describing each states’ segregation laws. Instead, they got a seven-hundred page detailed and comprehensive book, States’ Laws on Race and Color. According to Thurgood Marshall, Pauli’s book served as the “bible” during Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a direct challenge to Plessy v. Ferguson before the Supreme Court. Pauli’s former law professor, Spottswood Robinson, used her senior paper about Plessy as a guide to craft the argument that would ultimately bring down Jim Crow. The argument was exactly as Pauli had so boldly asserted as a law student years prior: whether racially segregated public schools were unequal and, therefore, violated the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees citizens equal protection under the law.

On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Warren delivered the opinion of the court. His words echoed Pauli’s law school argument from a decade before: “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children,” he wrote. Modern psychological knowledge made that clear. The court declared segregated educational facilities inherently unequal, a deprivation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection. Plessy was overturned, decimating the judicial justification for a “separate but equal” society and opening the door for lawyers and civil rights groups to continue challenging segregation in all its forms.

Pauli did not just help deal this fatal blow to Jim Crow but took on Jane Crow as well. Her legal analysis contributed to victories in pivotal women’s rights cases over the next few decades, including White v. Crook that barred the exclusion of women from juries. Pauli’s activism with the American Civil Liberities Union and National Organization of Women also ensured that discrimination on the basis of sex was included in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Over fifty years later, Pauli’s efforts continued to advance Civil Rights as “on the basis of sex” would be used in 2020 in the Supreme Court decision of Bostock v. Clayton County, protecting LGBTQ+ Americans from employment discrimination.

Pauli’s own identity likely influenced her defiance of rigid gender categories. Such categories did not fit Pauli. Her romantic relationships were with women, and she identified for many years as a man, despite never finding the understanding or support to live that identity more fully.

“Pauli Murray calls us to confront the way we even categorize and think about things,” says Barbara Lau, director of Durham’s Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice., Pauli’s life and work challenges the concept of courage itself. Courage is not a single act alone—”it’s a practice,” says Lau.

In 1977, Pauli embarked yet another career, becoming the first Black woman ordained by the Episcopal Church. “All the strands of my life had come together,” she wrote. “Descendant of slave and of slave owner, I had already been called poet, lawyer, teacher, and friend. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female—only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.”